The Universe of Master Composers – Strategies of Networking and Gendering in Ringstrassenzeit Vienna’s / Western Music Life

Introduction

Music history, as the story of western music’s relevance in the course of the 19th- and 20th-century’s so-called modernization, is – in an astonishingly consistent manner and in a way long outdated in other fields of historical description – still written as a series of heroic legends. This tradition determines, above all (but in no sense exclusively), popular descriptions and is, together with its significations, deeply engrained in practice, so much so that it is generally considered so-called conventional wisdom.

(cf. Also: www.worldhistory-poster.com/en/screenshots/classical_composers_500.jpg and www.haus-der-musik-wien.at)

Evidence of this circumstance is the fact that the narrative of western music’s chronology, of its periods, styles and genres, is mostly told in terms of and represented by grouped names of composers, almost exclusively male, in accordance with the standard for heroes in western civilization (exceptions like Joan d’Arc confirming the norm). Explanations for this gendering essentially (in both senses) point to differences in talent or intellect, lending a quality to this whole narrative that can be compared to the power of unchanging natural laws, of absolute truth: music can be seen, in this sense, as an art of western as well as of male origin. Neither assumption nor their implications are normally made explicit.

This contribution describes how and why western music’s heroic legend (a description still regarded as valid) represents western music-culture’s memory, its symbols, meanings and institutions. It shows how and why the 19th-century establishment of professionalized music life, together with its definition of a canon of master composers, is characterized by social mechanisms and role models that almost automatically exclude the non-conformist from a successful career, with women representing the group most consistently marginalized.

This article is, therefore, a case-study located in the time-space constellation regarded as the very focus of the development in question: namely, the 19th-century German-speaking region with Vienna as its mythical heart. Describing the networking and gendering at work in this history is a way of deconstructing the aforementioned legend and reconsidering some traditional assessments of the western musical heritage with the double aim of:

- critically re-writing music history, aiming to understand this music’s (ideological) function within the society it stems from and

- furthering the understanding of, and accessibility of, this music beyond its original socio-cultural conditions which have lost relevance (hence the difficulties that the classical music business has been experiencing, the boom in popularizing and even the existing interpretation as “dead white man’s music”).

Example (I): Classical music – Viennese classic

The most prominent and famous group of composers is doubtless the triad of Haydn-Mozart-Beethoven, seen as the personification of so-called classical music, that is, of western music’s center, culmination and pride.

The description of excellence in the arts as “classical” (originating in the 17th-century French querelle des anciens et des modernes) was adopted in music during the 18th century, but applied to different genres of music by different composers, and up to 1800 used to characterize musical quality in different periods. In the 1830s, in the context of German anti-French nationalism and parallel with the so-called Weimar classic in literature, a so-called Viennese classic was defined as a stylistic quality in music and identified with three names we still consider famous – according to the chronology of their deaths, i.e. first Mozart, then Haydn and finally Beethoven. At the same time the message spread that the capital of (German) music was the place where the important developments in music embodied by the three masters had taken place: Vienna. Classical music now meant this region’s instrumental music from the late 18th and early 19th century (the 1780s to the 1810s), characterized by unity of form and content, clarity of meaning, simplicity as well as artificiality, in short, music of universal value for mankind, representing the aesthetic ideal itself, which means form and content being as harmoniously balanced as feeling and understanding or, as we would say, as head and heart.

After the war against Prussia (1866) and the foundation of the German Reich (1871), this same term – Viennese classical music (style) – was used to externally identify and mark a differentiation not any more with France but with Germany (in the sense of Austrian Habsburg identity), while internally it represented the Gesamtstaatsidee as opposed to the particular national interests of the monarchy’s ethnicities. As a matter of consequence, it was also in the Habsburg residence of Vienna, where around 1900 the founding father of musicology as an academic discipline, Guido Adler, made the “classical style” historically and aesthetically a central category in his so-called Stilgeschichte, thus firmly establishing the term “Viennese classical composers” (Wiener Klassiker) in the young discipline’s literature.

This short excursus into the genesis of western music history’s most prominent term, which is as widely misinterpreted as it is popular, shows how relevant questions of identity, of nationally motivated inclusions and exclusions are for a cultural phenomenon (i.e. musical art) that has at the same time been mystified in quasi-religious terms as something heavenly and pure and thus to be regarded as being far above matters of politics and power. The iconography characteristically signifying romanticism’s emphatic notion of art-music can been seen in how the Viennese 1892 International Exhibition for Music and Theatre proudly demonstrated the “music-city’s” fame.

The further history of western music’s sanctification, of how classical music, its producers and distributors were canonized and its achievements in music life made a point of pride in the sense of cultural refinement, represents a means for and a symptom of the functioning of a network in which elitist art-music was both produced and consumed. In the case of Vienna, these processes took place against the backdrop of industrialization and urbanization, of the so-called second society’s cultural ascension in the 19th century and that of the middle class at the fin-de-siècle, and they can be described in terms of the forces governing this network’s use.

2) Brahms vs Bruckner – an example of successful othering

Post-1850s (western) art music is characterized by a conflict between two different approaches to the question of its so-called progress, its further development, which have been labeled the aesthetics of form versus the aesthetics of content. While contemporaries prominently named Johannes Brahms as the representative for the one side and Richard Wagner or Franz Liszt for the other, it is the standard version of conventional music history to personalize this conflict in the field of the then most prestigious form, the so-called Great Symphony, and name Anton Bruckner as the counterpart of Johannes Brahms (a staging that maintains the unity of not only time but also location).

These two composers represent the manifold structure of inclusion and expulsion in Vienna through art music, as this simple difference of aesthetic positions is placed in the context of social behavior, the relation between private initiatives and public spheres, and the discourse of identification. From the 1860s on, art music was increasingly defined in Vienna both as a cultural paradigm and as a cultural practice. The guiding force in this process was a group of well-established bourgeois and nobility that developed strategies and mechanisms to create and promote aesthetic norms for compositions and performances as well as the institutionalization of concert life.

Bruckner and Brahms each occupied a very different position in this network, and their respective standing in the culturally trend-setting Viennese society of their day has shaped the image of them that has been handed down to this very day. That society’s many cultural activities not only involved serving as an audience for plays, operas and concerts, but also its hosting of private soirees for artists of different kinds, a very important activity in this field as the situation of an artist in Vienna depended to a high degree on the network of private relations established at and by such occasions.

In the case of Johannes Brahms, such relations determined the first steps he took in Vienna in 1862 (cf. the music critic Max Kalbeck’s biography of Brahms, published in two volumes in 1903 and 1907). It was a certain Bertha Porubszky, who before moving to Vienna had been a member of a women’s choir he conducted in Hamburg, whom Brahms visited right after his arrival. Porubszky showed some of his music to one of Vienna’s most important pianists, Julius Epstein, and encouraged Epstein to make the composer’s acquaintance. The two men agreed upon a rehearsal of the pieces in question in Epstein’s apartment, and Epstein (who happened to live in the house Mozart had lived in between 1784 and 1787 and composed the Figaro and the Fantasy in C-minor) invited for the occasion Vienna’s most important string quartet, led by Joseph Hellmesberger (himself a child prodigy of the 1830s) together with some friends (it is really remarkable how decisive this dense climate of classical tradition and its relevance for a certain social group must have been for Brahms’ situation). After this rehearsal Hellmesberger and Epstein agreed to perform at Brahms’ public debut and, as a result of the concert’s success (mainly due to Brahms’ talent as a performing artist, not as a composer), Epstein rented the Musikvereins-Saal (not the famous Golden Hall, but the hall at the former building of this association) without even asking him. Some ten days later, Brahms had another public performance. Obviously a concert could be organized very quickly in those days of developing professional music life, when institutions of music management were not fully established and private activities prevailed.

Anton Bruckner’s move to Vienna happened under rather different auspices. He had visited the city twice during the six years of his studies (1855-1861) with Simon Sechter, the best-known teacher of the time, whom Schubert had contacted for this purpose before his death in 1828. These studies are said to have taken Bruckner about 7 hours a day, in addition to his job in the upper Austrian countryside and his taking lessons with the conductor and musician Otto Kitzler. In 1858 Bruckner (at the age of 34) passed a first exam with Sechter and performed in his first public concert as an organist in Vienna. Only five years later, in 1863, did he regard his studies as completed, and he moved to Vienna to continue his musical career in the place he (and most of his Central European contemporaries) regarded as the very center of music life.

A look at the two composers’ subsequent careers reveals a remarkable fact: in art music in the sense of the romantic concept (the original work of genius represented by a great symphony), posthumous fame in the sense of inclusion in the pantheon of music masters as well as a successful position as an acknowledged composer of art music was not and is not defined by the categories of aesthetic norms and qualities – as the cliché would have it – but rather is negotiated within the frame of groups empowered with defining norms and standards culturally as well as socially. It is evident that, although as composers of art music both Brahms and Bruckner belonged to elite music life at the same time and place and shared the idea of the great symphony’s importance as the most prestigious form, it was their belonging to different social networks that resulted in the different positions they achieved in music life, their different careers, and above all the different reputations they garnered not only in their life-times but, above all, in posterity’s awareness.

As mentioned in my description of their respective first steps into Viennese concert life, Johannes Brahms and Anton Bruckner were of different origins – the former from urban Hamburg, the latter from rural upper Austria. They also differed in religion, resulting not only in different religious practices (Bruckner’s intense Catholicism being well documented), but even more in different approaches to authority, different options for positions in music life and in different habits which brought them into contact with different social networks in Vienna.

Even their respective positions as performing artists helped to shape these differences. Anton Bruckner was an organist and, on account of this instrument, was closely identified with teaching, in the sense of the craft of composition, i.e. harmony and counterpoint. As these functions signified the traditional composer’s positions, they also characterized his professional image in the sense that, together with the Catholicism he practiced and his acknowledgment of imperial authority (regarded as outdated at that time), Bruckner was well prepared for a career both as a teacher of composing techniques and as a musician in courtly positions. Accordingly he started teaching at the conservatory and even the University of Vienna (music theory) and achieved the positions of second archivist of the royal chapel ( Hofmusikkapelle 1875), of second singing-teacher of the royal boy’s choir and of courtly organ player (Hoforganist 1878), always asking for financial aid to support his symphony-writing by freeing him from daily labor. An important characteristic of his symphonies is their link to religion – Bruckner tried to realize the baroque idea of the connection between earth and heaven, to write music in praise of God, not only sacred music but also his symphonies, which he dedicated to ask for the protection of important people and finally, also, of God:

1. Symphony (Viennese Version): University of Vienna

2. Symphony: no dedication as Franz Liszt seems to have forgotten about Bruckner’s request

3. Symphony: Richard Wagner

4. Symphony: Prince Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst, Obersthofmeister

5. Symphony: Dr.Karl von Stremayr, Minister of Education

6. Symphony: Dr.Anton von Oelzelt-Nevin and wife

7. Symphony: Ludwig II, King of Bavaria

8. Symphony: Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria

9. Symphony: to dearly beloved God (“dem lieben Gott”)

When Brahms came to Vienna as a pianist, he was, from the start, better integrated into professionalizing concert life than Bruckner, chamber-music playing providing interaction with other, well-established performers and at the same time being THE cultural practice within trend-setting society’s private activities. Accordingly Brahms became a leader within the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, THE group around which the city’s music life circled and developed. Becoming the artistic director of the Gesellschaft meant having not only a good annual salary, but also one of the three top positions in Viennese music life (besides the directors of the Royal Opera House and the Royal Chapel). It meant being a main player in the field, not only responsible for all artistic questions within the Gesellschaft, but also for choosing professors for the conservatory, the awards of state scholarships to musicians and the winners of the Beethoven Award. Considering the importance of public opinion in contemporary society, it adds to this picture of successful integration into a system that three important music critics were Brahms’ friends (Eduard Hanslick, Richard Heuberger and Max Kalbeck), all of whom helped the circle to dominate the setting of the norms and standards of music and music life. This group could control – by the means of an association especially founded for that purpose (the Wiener Tonkünstlerverein), with Brahms as its honorary president – every composer and every musician who set foot in Vienna and every new piece of music written there, as evaluations were already stated within that group before the first public appearance or performance.

Johannes Brahms’ career can thus be understood as a reflection of the opportunities provided at that time by a music-loving urban society, one which never accepted Bruckner in spite of his many official positions, but regarded him as a strange, funny figure. Remarkably this difference in social standing – with Brahms the urban, state-of-the-art figure of modern Ringstrassen-Gesellschaft lifestyle and Bruckner the traditionally oriented, rural Austrian, whose lifestyle (and financial means) never allowed him to be part of the society on which contemporary urban music life was based – is opposite to both composer’s aesthetic positions, Brahms being the traditionally oriented, conservative composer and Bruckner the advocate of musical progress in the sense of so-called Zukunftsmusik (which at this time was discussed by German composers associated with Franz Liszt but had its center in Richard Wagner’s “Musikdramen”).

The defining importance of social rank for recognition as a prominent composer can be further illustrated with the case of Johann Strauß, who worked in the less prestigious field of commercialized music entertainment but had a successful international career in the modern, urban sense and, therefore, himself became the center of an equally flourishing but mostly separate network of music life. Strauß adopted the lifestyle of the “second society” and was in contact with Johannes Brahms and his circle from 1871 on. When in 1892 the composer Ignaz Brüll’s family left their summerhouse in Ischl, Strauß came with his young wife to rent it, and the following year rented the villa of a Count Erdödy, which three years later he even bought. Brahms, who was a frequent visitor in the summer residence as well as in the Strauß’s Viennese apartment, esteemed in Strauß what he thought to be a characteristic Viennese talent, namely the sound of the waltz-band, the “Mozart-like” instrumentation. Brahms attended every premiere of a Strauß operetta, participated in the celebrations of Strauß’s Golden Jubilee as an artist in 1894 and gladly accepted for his prominent collection of music autographs three of Strauß’s waltzes as a present.

Comparing the three composers’ careers and posthumous images makes clear that while the socio-cultural and the aesthetic rely on different norms, the mechanism of inclusion and exclusion within a system central to Vienna’s identity – the notion of “a music city at its prime” being a politically based self-awareness well documented in memoirs and travelogues – also shapes the historical narrative meant to describe aesthetic qualities on which the canonization as a master of the musical universe seems to be based.

This means that while Anton Bruckner has in the meantime received his place in the musical museum – due to his rank as a composer of great symphonies, he, too, has his complete edition and his share of admirers; and his anniversaries are the subject of special events – his social marginalization is still relevant whenever biographical details come into play (cf. the role of anecdotes, of personal remarks recorded, always in dialect). Johann Strauß, on the other hand, although working in the aesthetically less acknowledged field of commercialized entertainment is part of the national pantheon of music masters due to his lifestyle, but also to his commercial success. His heavily gilt monument in the Viennese Stadtpark documents his inclusion into the very heart of the musical universe, at least as a figure represented in Vienna in the sense of the music capital topos.

To conclude, the world of art music – as traditionally built within the frame of concert-life, of professional music education, of practices of composing, of performance and of music appreciation – can thus be seen to be a network that is premised on the social preconditions of urban civil society. It works to set the norms and standards of this art and governs the mechanisms of representation of cultural values as well as art music’s ideological function for the definition of mainstream culture. Creating works of art in music in the romantic sense is, in the first place, a question of talent and of technical knowledge, but the rank one achieves in public, both during one’s life and posthumously, depends on one’s position in the social network of the dominating culture. The difference between the pioneering times of bourgeois music life and the current situation lies in the overwhelming role of recorded, mediated music, which has led to a historically unique situation of a diversified repertory stretching far into the past that results on the level of reception not only in the enhancement of that repertory but also in its ever more rapid changes, both of which draw attention to the seemingly eternal canon’s transitoriness. Agents in this field are, therefore, not only the composers and performers, but also the mediators, both those with a function in music life, such as music critics, managers, organizers and, in the course of the media’s development, producers of storage mediums, and those with positions in the academic field of music history, where editions, articles and the like not only reflect but also shape public awareness and evaluation. Excellence in the field of composing (the rank of a “master of the universe of western music”) is ascribed both according to (1) a production regarded as state-of-the-art both in artistic means and forms, prestigious genres changing in the course of history with social functions and symbolic meanings of music and (2) the position in contemporary music life, which itself represents a network of socio-cultural importance governing aesthetic norms. All of this said, two things become clear: this network has different hierarchical positions in regard to contemporary awareness as well as – often differently – in the eyes of future generations. For the music city Vienna’s period in question, there are:

- the other composers of the Brahms circle, well established in contemporary music life by the same aesthetic position and their close relation to Brahms, but who specialized in different genres and were judged second rank by the same circle’s opinion (defined by Brahms himself), namely:

- Ignaz Brüll(1846-1907): a pupil of the already mentioned Julius Epstein, one of Brahms’ first contacts in Viennese music life, he composed piano pieces that were standards in typical contemporary collections for private music-making and 10 operas, some of which are still performed. He was Brahms’s favorite pianist and used to play his orchestral scores with him on two pianos, to give his friends a kind of “sneak preview.”

- Carl Goldmark (1830-1915): When he met Brahms in 1860-61, he had already made a name for himself with his String Quartet op.8 and played the viola in the string-quartet which Brahms gave his new quintet for a first rehearsal. As a composer Goldmark was a local authority (more than Brüll), famous for his first big score, the opera The Queen of Sheba (1875), and for some orchestral pieces. He also wrote chamber music, both vocal and instrumental, and was part of that vivid scene of private music-making.

- other contemporaries that have not only been forgotten because they would have worked in less artistically prestigious fields and/or have been less talented, but because their careers did not, for various reasons (physical, psychological), continue. Some of these occasionally emerge from the shades of memory when discovered by some researching musicologist or musician at the “right time” in the sense of seeming relevant to contemporary ideas and significations (cf. Gustav Mahler, Hugo Wolf, or the recently “discovered” Hans Rott, all of whom belong to the same generation).

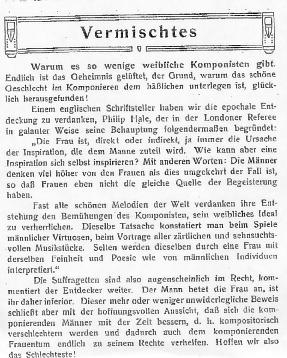

The oft discussed lack of many and prominent female composers is exactly based on and caused by the aforementioned conditions of this art music network. Contrary to the cliché, it is not a lack of talent (often said to be based on different intellectual qualities) that prevented women for a long time from having successful careers as composers. Rather this is due to different social positions/options and a different image in society, fundamental to candidates for the pantheon of western art music. The mechanisms of exclusion and othering active in this field apply particularly to women – compare how important the strict norms of the modern urban citizen were that enabled Brahms to make use of all the opportunities in music life at hand and how reduced these options were for a man of a different origin and lifestyle like Anton Bruckner, and then imagine the difficulties a woman would have faced, who was already the other to the male role model on account of her sex. The long-standing discussion over and search for prominent female composers is, therefore, comparable to the search for prominent composers outside the Germanophone realm defining the mainstream, composers marginalized by the term “national schools.” Both of these forms of exclusion take the frame of the heroic legend as the decisive basis for judgments that are said to be based on criteria of artistic, aesthetic quality, and both have been defended with the strangest reasons (cf. the following clipping of Wiener Konzerschau, Dec. 1911)

Applying a network perspective to music history’s tradition reveals the complicated structure of these processes and helps us identify the bundles of different criteria effectively at work.