Meeting

Through Time and Space:

The Kirschner Letters, 1925 – 1973

October 1, 2003

Edmonton, Alberta

Dear Karen:

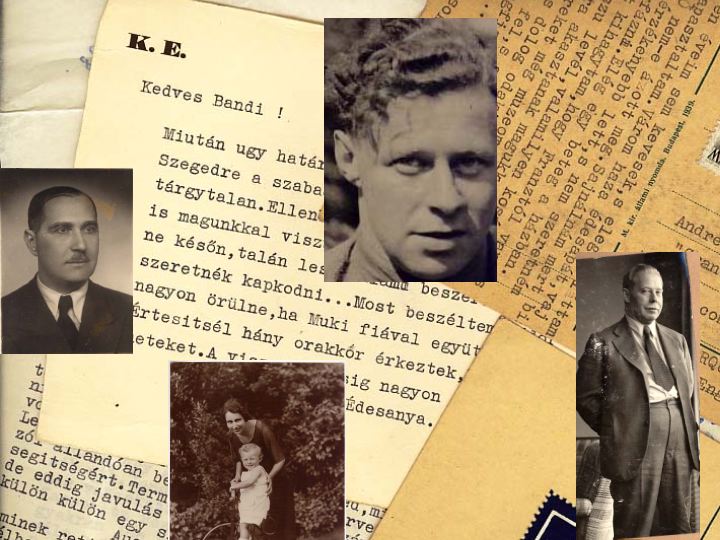

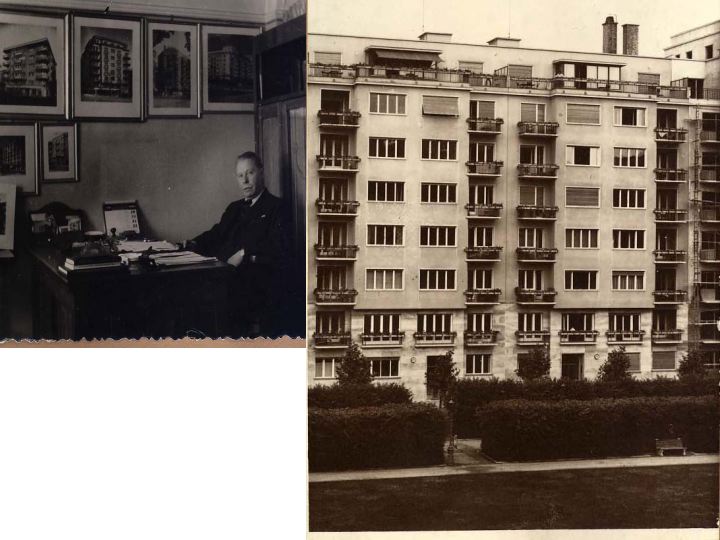

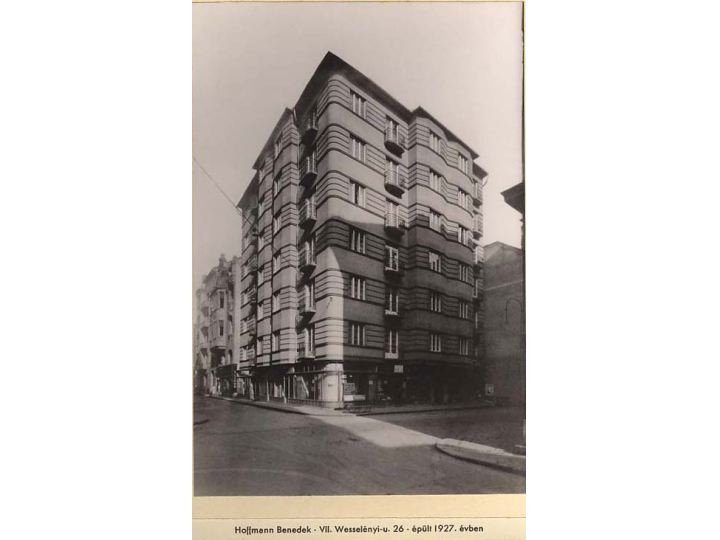

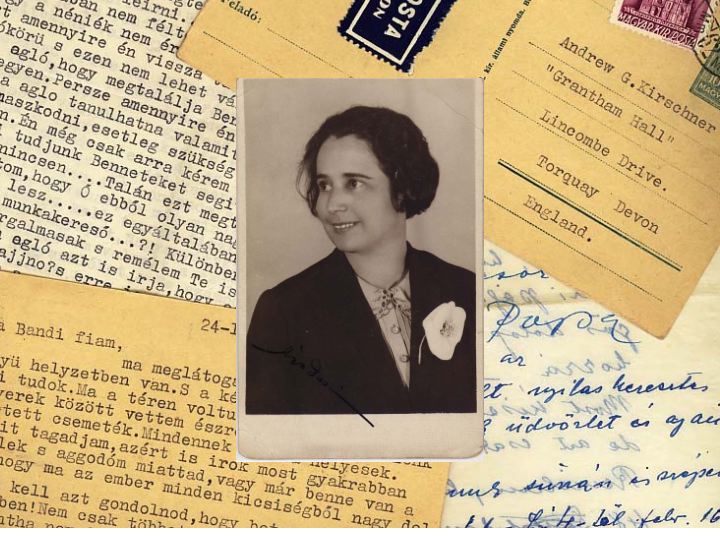

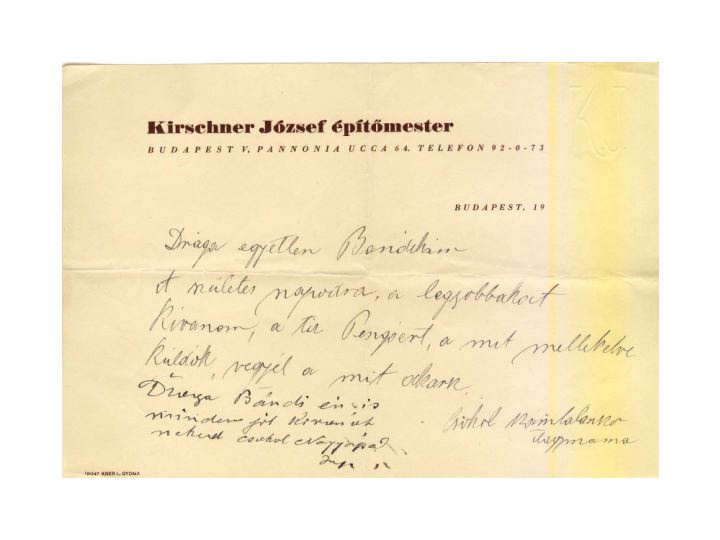

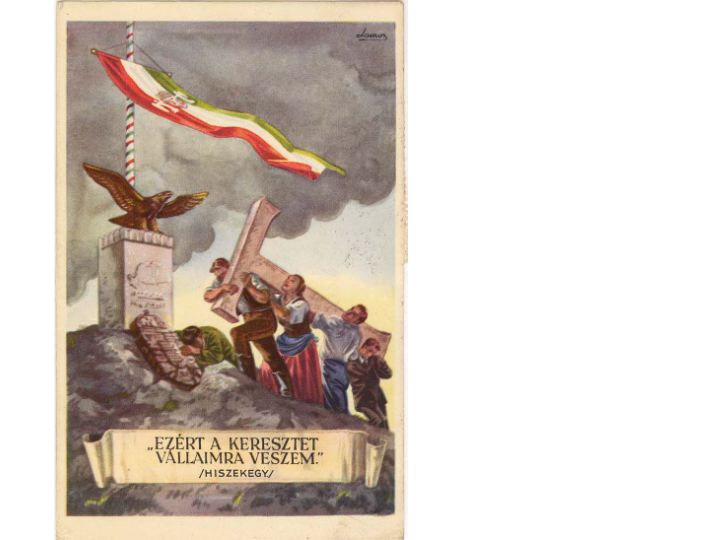

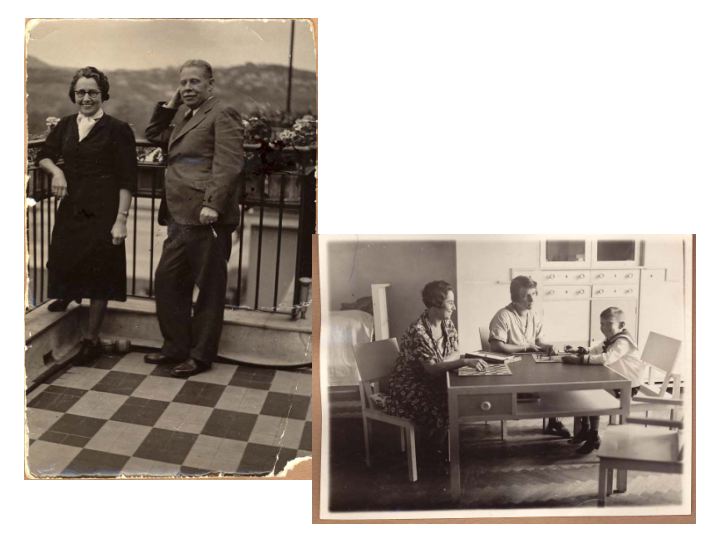

What excitement last night! I took that exquisite portfolio of my grandfather’s to Szidonia and Gabor's. Do you remember it? Assembled in 1940, it’s a huge boxed tome of 59 elegantly bound photos. They are portraits of the Budapest buildings designed by my architect grandfather in his early career. A small brass stamp inside the cover identifies the work as that of my grandmother’s cousin, respected Hungarian-American bookbinder, Elisabeth Kner.

We were meeting to discuss the continuing translation of my father’s letters, and Szidonia and Gabor had expressed an interest in seeing the portfolio. As Szidonia examined the photographs, she suddenly froze, then blurted out her discovery. The photo she was looking at was her Budapest home. She had grown up and lived most of her life in a building that my grandfather had designed. The idea seemed so fantastic, the possibility so remote. What were the chances that Szidonia, a stranger until a couple of months ago, and I would ever meet, let alone discover a family connection that now binds us in some way?

All this takes me back to so many of our discussions about identity. What is identity, anyway? Why do I plague myself trying to solve, or resolve, mine, why should I care? Is identity really about ancestral pedigrees and bloodlines? Why do we talk about lines and linearity, when the natural world has always been web-based, venous, more about networks than anything else?

Szidonia’s discovery drew attention to a filament in my web that was already there. I just hadn’t noticed it before. When I started looking for a translator for the letters my father exchanged with his parents, whom did I find but someone already connected to me? And how strange that you should introduce me to Szidonia and then that your family name should appear in one of the letters.

As we’re contemplating these letters together now, perhaps it would help if I tell you my father’s tale again, at least the story of that decisive moment when he literally gave up his identity.

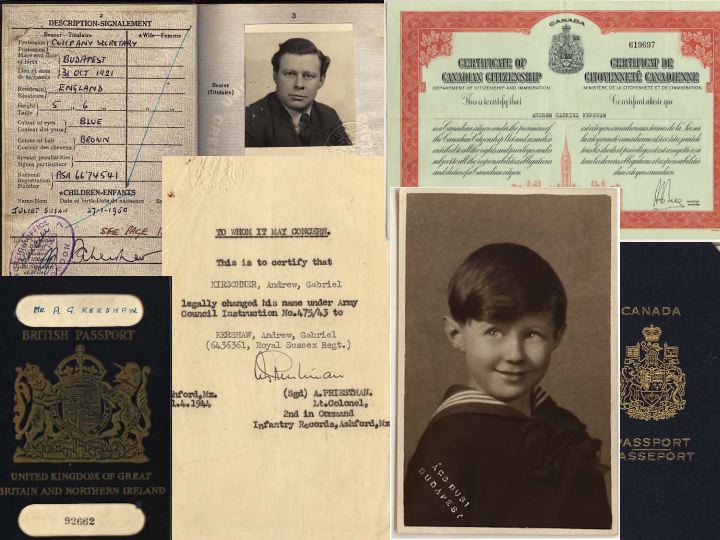

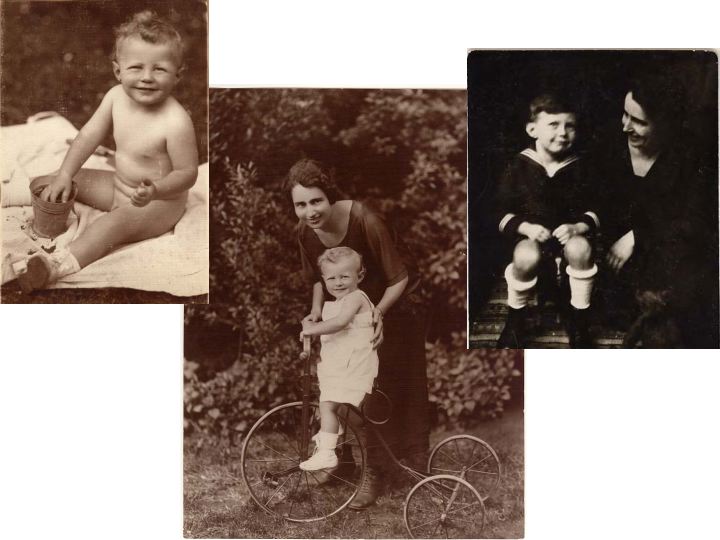

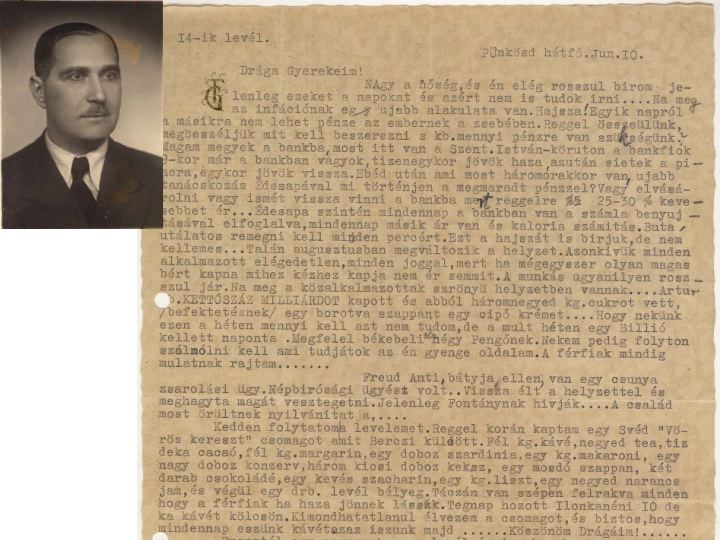

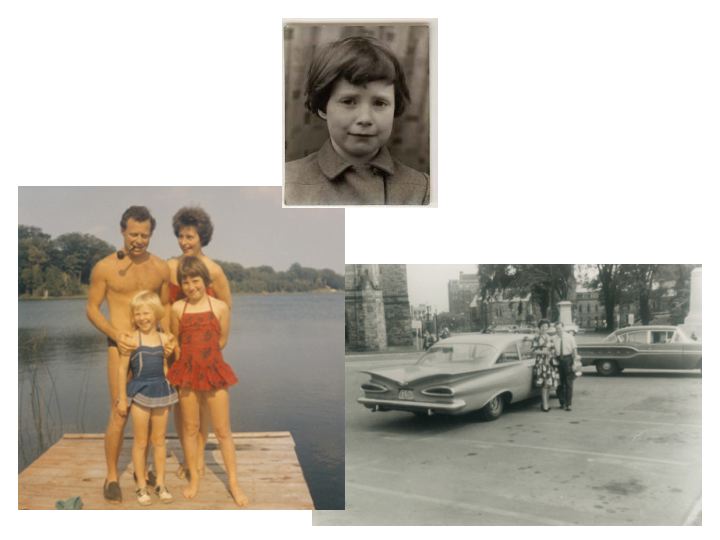

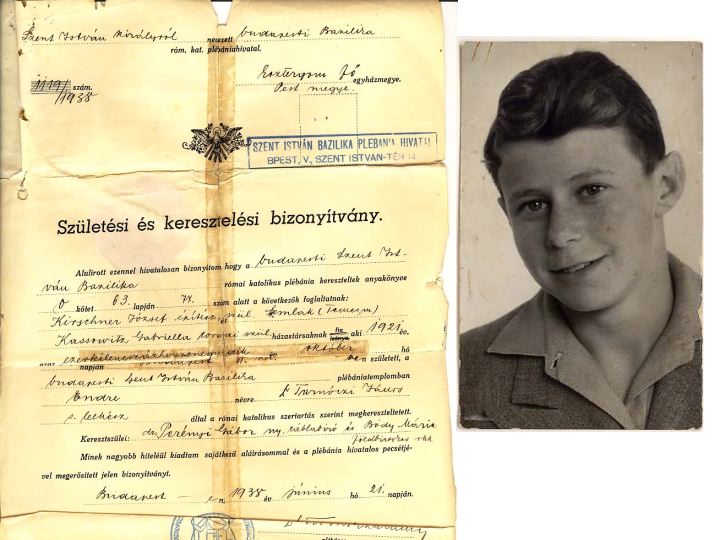

As you know, my father, Endre Kirschner, nicknamed Bandi, was born in Budapest in 1921. Though he was Jewish, his parents followed common practice and had him baptized Catholic, apparently much to the ire of his maternal grandfather. Raised in a pampered upper-class environment, my father at 17 was well-educated, fluent in three languages, athletic, cocky, independent and ambitious. When the Nazis marched into Austria, my grandparents realized the threat and sent him to Torquay, England, to finish his schooling. Once war broke out, like thousands of other Europeans living in Britain, he was classified as a “friendly enemy alien.” Though his Hungarian citizenship saved him from the internment that Germans suffered, he was not allowed to sign up for active military duty. Instead, he was permitted to join an unarmed unit called the Pioneer Corps.

The Pioneers attracted many young men like my father, from all over Eastern and Central Europe, all eager to rid the world of Hitler, but not allowed to fight. Eventually, the British Admiral Mountbatten realized the advantages they could provide to the war effort, and he allowed them to join the British commando units, which carried out covert anti-Nazi activities on the continent.

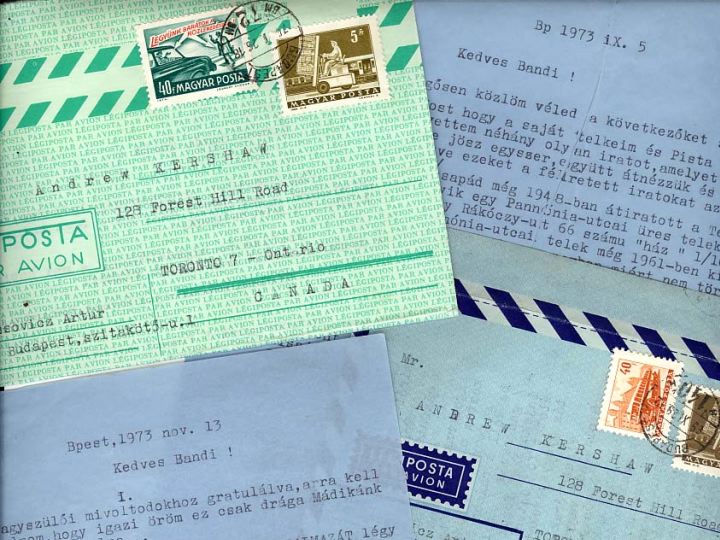

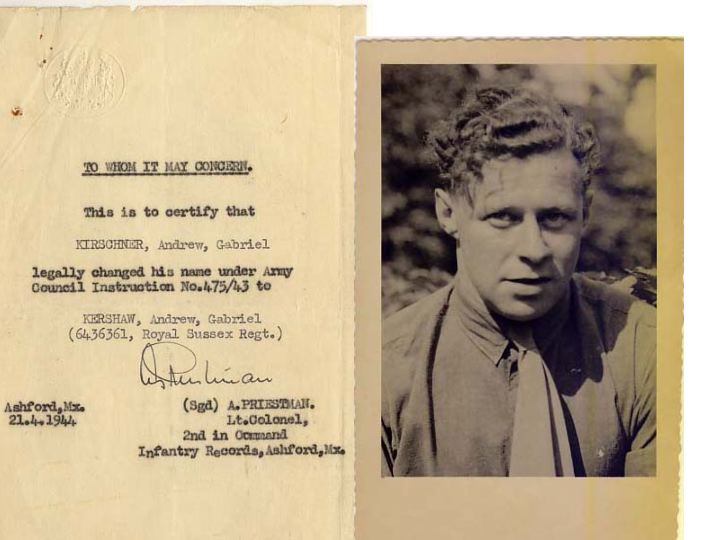

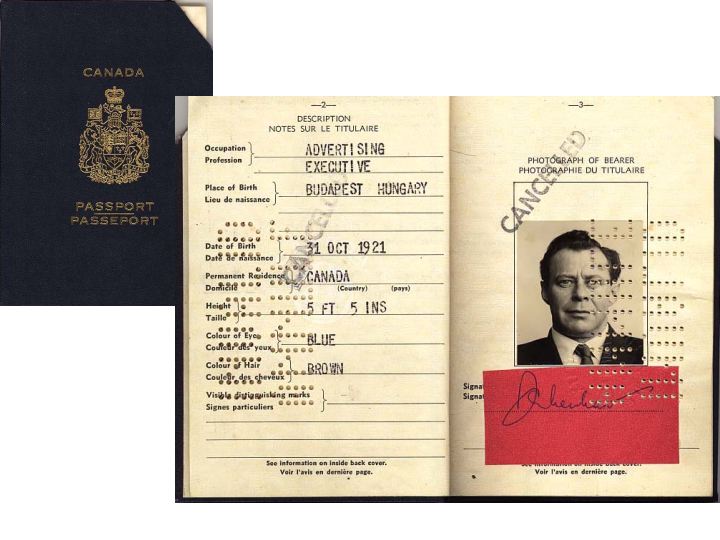

Thus it came about that one day in the spring of 1942 my father shed his identity as Endre Kirschner of Budapest, Hungary, a Jew, and became Andrew Kershaw, British subject, belonging to the Church of England, an army commando and member of X-Troop. He was given one hour to choose a new English-sounding name and warned to never again refer to himself by his birth-name. He had to construct a new family history and burn any possessions that could reveal the truth.

It must have been an astounding moment in my father’s young life when he relinquished his entire past: Here I am, Endre Kirschner. I have an hour to choose a new name. Scramble for the phone books outside the meeting room for ideas. Reassemble. The Skipper, our commander, says I have 24 hours to create a new life story. A fiction. I am 21 years old; tomorrow I will be reborn.

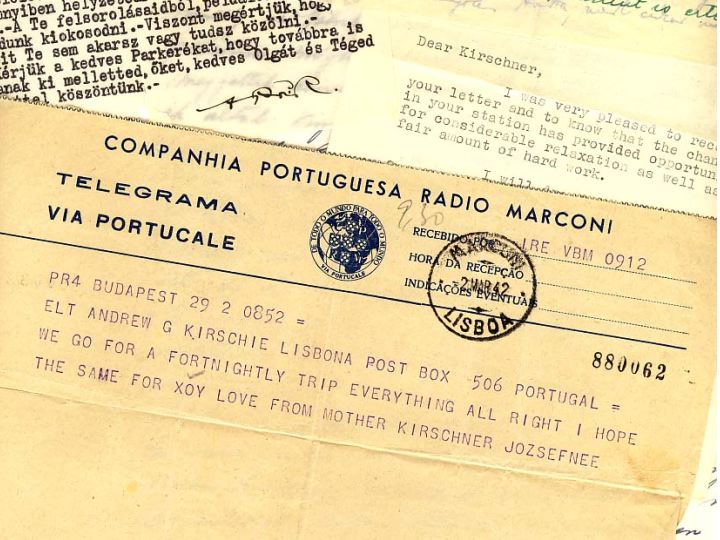

Through an elaborate counterfeit system, my father and his parents managed to exchange letters throughout the war. Until recently I had no idea of the contents of the letters. I was hoping for great revelations: about family members, about my father, about where he came from. But from what you, Szidonia and Gabor tell me, the letters are remarkably unspectacular.

Now I ask myself, what was I really expecting?

When I look at my father’s story as revealed by these letters, I see networks that were invisible before. The international support system of friends and relatives that funded him away from home. Another network that helped my grandparents survive after the war and through the worst of the Communist era. Web strands continually reveal themselves in North America. One day a few years ago, a stranger called my sister in Vancouver and introduced himself as our cousin. He was announcing his family’s recent move to the city. She called me shouting, “We have a new cousin, cousin Eric!” But really, what is Eric to me? Another unanticipated web strand, newly revealed and there for me to investigate, if I choose. Is he a kindred spirit because we are blood related? After meeting him, I feel I will find a greater kindred spirit in Szidonia, with whom I share no physical connection but a psychic one.

I’m beginning to understand what I want from the letters. I’m hoping they will allow me to develop a feeling for the authors, some kind of connection. Will the letters reveal my grandmother’s identity? And is she a kindred spirit?

Read on, Karen and Szidonia! I’m curious to know more.

Juliet

October 10, 2003

Edmonton

Dear Juliet:

When I started reading the letters, I kept hearing the words from a poem by a long forgotten British poet, called “To a Poet One Thousand Years Hence.” It's written as a letter addressed to kindred souls of the future that he, the poet, would never meet. I still remember the first and last verse:

I who am dead a thousand years,

And wrote this sweet archaic song,

Send you my words as messengers,

The way I shall not pass along.

Since I can never see your face,

And never take you by the hand,

I send my words through time and space

To greet you. You will understand.

I couldn’t help but recall the notion of words passing through time and space when I read your family letters, and I have relished this chance to become part of your father’s and grandparents’ world, something they clearly could never have anticipated.

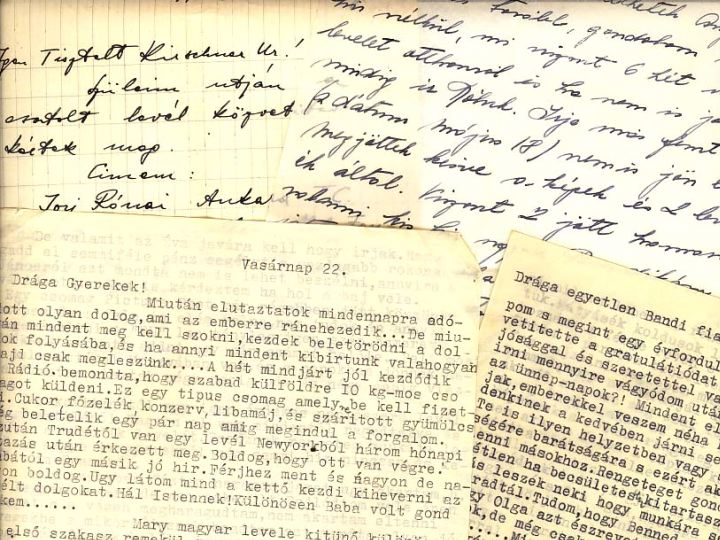

As you know, though many of these letters were written in a traumatic time in world history, there is little of the political in them, with the exception of some of your great-uncle Arthur’s bitter comments about forced labor and his criticism of those who mouth the platitudes of Christianity but do not practice the ideals. The constant talk about weather and house guests and opera seem to have performed the vital function of preserving a sense of normalcy in the midst of terrible times, especially for Jews. One passage from a letter your grandmother wrote to your mother, her English daughter-in-law, sticks in my mind: “Mary,” she asks her, “are men’s hats going out of fashion in London?” And she goes on to talk about how hats are falling out of favor in Budapest. She hopes that is not the case in England.

Maybe this is what we need letters to do — tell us that everyday life continues, that people notice fashion and go to the opera, that there is a sane core beneath the mad surface of life. In this way, letters seem to function as talismans against the death of the other.

As I know now, one of the reasons for the apolitical nature of the letters was the need for secrecy because of the possibility of interception by the Nazis. Letters assume privacy and uninterrupted passage, but that is so often not the case. In fact, letters can be weapons, as I was reminded recently after reading a curious little book by one Katherine Kressmann Taylor published in 1939 called Address Unknown, a novelette written entirely in the epistolary form. The correspondents are a Jewish man living in the States, Max Eisenstein, and his German friend, Martin Schulse, of Munich. Though they initially are friends, Schulse becomes a fascist and betrays Eisenstein’s sister to the Nazis. Instead of breaking with his fascist friend, Eisenstein begins to bombard Schulse with letters and telegrams, praising him for being a friend to the Jews and giving him frequent financial reports of his non-existent investments, playing upon and recuperating the historical prejudice against Jews as greedy and acquisitive. Despite Schulse’s pleas to Eisenstein to stop writing — they both knew that the letters were being read — Eisenstein continues his subversive campaign. Finally, his last letter to the friend who betrayed him is returned as “Address Unknown.”

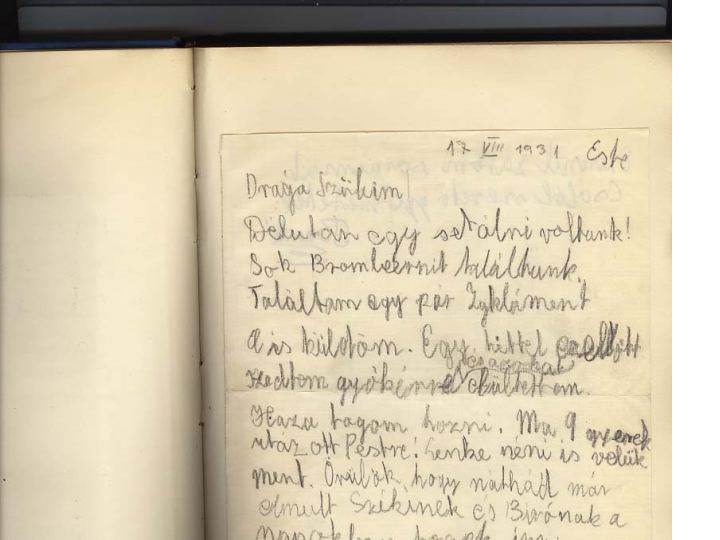

Letters can involve a private language. Perhaps there are subtexts in these letters that none of us, not even fluently bilingual translators, can recognize because it is a private and now lost language, a meta-language, if you will. Maybe that innocent comment about hats meant something else altogether. For example, there is one short letter from your father to your grandmother, which he composed while at summer camp in Austria, in which he talks about going to school with his “feher kuttal.” I asked Szidonia what this phrase meant and she was baffled; she postulated that it was a pet name for something, a family in-joke. We’ll probably never know.

In the very way they are folded, in a small tea stain in the corner, in the lick of a stamp, letters signify the physical absence of someone, they represent another in their physicality, their tangibility. We can caress the paper on which they are written and smell the ink. Obviously, you’ve noticed the metaphorical way in which the quality of paper the letters were written on changed from the fine vellum of the pre-war letters to the scruffy, rough paper that came later.

It really struck me, too, that most of the letters were typewritten. This made it easier for me, with my conversational Hungarian, to read them, and I was impressed by how few errors there were. Imagine typing away in the middle of a war on manual typewriters without a correct function, and producing coherent letters with few typographical mistakes. I had a striking reminder of this the other day when I went to visit Mrs. Botar. You remember my 90-year-old Hungarian friend, a still living contemporary of your grandparents, who also was in Budapest during the war? She had just received a letter from Budapest from her 91-year-old friend, which looked amazingly like one of your grandparents’ letters. It could have been typed on the same typewriter. As I read it aloud to her, I recalled Marshall McLuhan’s words about how the rhythm of typing favors short, terse sentences with oral form. McLuhan also said that the book is the extension of the eye, and electronic circuitry is the extension of the central nervous system, which would mean, surely, that the typewriter is the extension of the hand. I like the humanity of that image.

Actually, Juliet, it was rather strange reading your family’s letters – as though I were eavesdropping on a conversation. After all, they weren’t meant for a third party. They were meant for the addressee and the writer, who writes as much to himself as to his intended recipient. Letters exist in relationship with one another; they expect a response. The American writer John Barth wrote that, “We converse to convert, each the other, from an Other into an extension of oneself.”

I am not the only unintended and unimagined audience to your family letters, though. You inherited a stack of letters written to other people in a language that you couldn’t read. You gave the letters to translators who were able to read them but had no vested interest in them. And I was in the middle, wanting to read them, but getting especially lost in Arthur’s sophisticated prose and sly jokes. Still, there were some interesting connections made, weren’t there? Szidonia not only grew up in a house built by your grandfather, she also went to college with the daughter of one of the men mentioned in the letters. And even though the Virags who hid your grandparents for several weeks are probably not related to me, I am glad they weren’t fascists.

It strikes me, too, that our stories our somewhat similar, both daughters of a non-Hungarian mother and a Hungarian father. Our families are even from the same area of Hungary, Erdely, now part of Romania. Your father had a secret past and eschewed his Hungarianess, so that aspect of identity was not meaningful to you till you were older, but what about the revelation of your Jewish background? Did it change your conception of yourself? British journalist Christopher Hitchens had a similar experience — in 1988, shortly after a pro-Palestinian book he edited with Edward Said was released, he discovered that his mother was Jewish, an experience he describes in an essay entitled “On Not Knowing the Half of It.” His discovery brings pleasure: he invokes the names of three great anchors of modern, revolutionary intelligence — Marx, Freud and Einstein — who all just happen to be Jews, and, Hitchens, not being known for his modesty, traces a line from the great Jews in the internationalist tradition to himself. Still, the way is fraught with peril. Did he ever tell a Jewish joke he wouldn’t have told if he had known his mother’s identity? What about his avowed atheism? In the end, Hitchens embraces what he calls a Jewish collective memory — the knowledge that the worst can happen.

And what does the Hungarian connection mean to you? Do you consider yourself Hungarian? Given the Canadian multicultural mosaic model, many Canadians’ sense of identity is expansive and fluid but occasionally uneasy, too. Canadians are so diffident and spend so much time wondering how to define themselves. In fact, this constant need for definition is perhaps what it means to be Canadian.

But I have gone on long enough. Too much navel-gazing gives one a stiff neck. Besides, it’s time to check the mail! The real mail, that is.

Karen

November 3, 2003

Edmonton

Karen,

Sorry. I am at my computer and must reply by email. No friendly envelopes to greet you when you next check your mailbox.

You asked in your last letter if I feel Hungarian. No, I don’t, but like many Canadians, I do suffer a certain degree of cultural confusion. We immigrated to Canada from England in 1956 and, presto, five years later I was a Canadian. A British sensibility rings familiar to me because my mother was English and I lived there until I was six, but I certainly don’t belong there. As for my Hungarian heritage, it is as alien to me now as it was when I was a child. I knew my parents were somehow different from my friends’ parents, whose families had lived in waspy Toronto for generations. However, despite my father’s dramatic and fantastic life, I’d never heard of him or his family suffering any deprivation, and I had no inkling of the Jewish connection either. My father embraced his life in North America with such energy, there was no time to even peek backwards. The silence avalanched when he died at the age of 57. I think I’ve been digging my way out ever since.

I have often wondered if my cultural confusion – and that’s the hallmark of being Canadian if ever there was one – is my father’s unintentional legacy to me. I must admit, though, that my breath caught in my throat when I read the conclusion of Hitchens’s essay, when he wonders whether he occasionally “felt” Jewish because of some Jewish collective memory – the idea resonated so strongly.

Years ago, I heard a CBC documentary about the children of Jewish refugees from the Second World War. Whether or not their parents had been in concentration camps, the people interviewed all described growing up and continuing to live with feelings of inconsolable sorrow. Their misery was compounded by an inability to attribute their overwhelming sadness to any specific life event or circumstance. I realized I was one of those people.

No doubt, my father was profoundly changed by his experience of exile and war, but like many survivors of trauma, he spoke of neither. I wonder today if the profound but unacknowledged effect my father’s forced exile had on him is largely responsible for my difficulty identifying any spot as home.

So, where do I belong? Well, Canada is more familiar than anywhere else and my children were born here. Yes, I hear the diffidence. Guess I am home, after all.

Juliet

November 16, 2003

Delhi, Ontario

Dear Juliet,

I am writing this from my hometown, a tobacco town in southern Ontario, a mere 3000 kilometres away from Edmonton. Stopped for lunch with my cousin at the local Hungarian hall, called the Magyar Dohany Haz, the Hungarian Tobacco House. Many European refugees, including more than 6,000 Hungarians, moved to this area after the war and established themselves as tobacco farmers, my family among them. My father was the one charged with maintaining correspondence with the relatives back in Hungary. While my grandparents were not illiterate, they were peasants and lacked the education, and probably a certain aesthetic sensibility, to worry about writing letters, or at least letters that diverged from the conveyance of basic information regarding births and deaths. Letter writing, then, like everything else, is a class issue. I have some larger-than-life memories of my Hungarian grandfather, who used to eat peppers so hot that he cried in joy and ecstasy and who was once investigated by the RCMP for growing poppies, but sadly, I have no letters at all — written or typed — no ornate signatures, just a few photographs. In this age, in which the image is replacing the word, perhaps this is natural.

And speaking of larger than life, thanks for lending me that Anna Porter book, The Storyteller: Memory, Secrets, Magic and Lies. A Memoir of Hungary. I loved reading her tale of growing up in Hungary and of her grandfather who told such marvelous stories about the mythical Hungarian past. The Hungarians excel at mythologizing themselves, something at which Canadians are pitiful. Essentially, the book reads like a love letter to Porter’s grandfather and to her own childhood, as an attempt not only to recount her life but to preserve memories. Still, memories form an unreliable narrative, underneath which the ground continually shifts.

In the case of your family letters, I imagine that now that your parents have both passed away and your children are grown, understanding this story is more and more important to you. Yet, your letters remain fragments of a longer narrative, a discourse that never ends; unlike those Matrioshka dolls, the doll within a doll within a doll, this is not a matter of peeling away layers of meaning but of adding another strand to a tapestry.

That’s enough tropes for one day. See you back in Edmonton.

Karen

November 24, 2003

Edmonton

Dear Karen,

Yes, you’re right. We are weaving even as we dig. I want to know that I’m part of an ongoing story. I know, of course, that letters can provide only a glimpse of the whole story. Yet in the case of this stack of my father’s letters, their translation will resolve something for me. Untranslated, the contents were a mystery; I could imagine they contained whatever romantic tales I wished. Translated, they ground my flights of fancy and flesh out the images in old photo albums; I can hear my grandparents’ voices. The letters provide me with a context for a crumbling world, within states and families. Letters were the only substantial, tangible connection left for the parents and son to cling to, during his exile, the war and finally his emigration to Canada. Now I cling to the letters. Even if I never understood a word of them, those letters offer tangible evidence that there once was family, my family, and they cared enough to write and write and write to each other. It’s all about transubstantiation.

Once these hundreds of letters have been translated, maybe I will have some stories to pass on to my children, or maybe I’ll take to spinning, as Anna Porter did, a web of magical tales and family lore. Besides the letters, I have that portfolio, after all. I can still hear my mother telling us: “Your grandfather survived the war because he built most of Budapest, you know! He was too important to do away with.” Myth or truth? The letters don’t tell. But they fasten the strands, the better to spin on.

So now, Karen, you have to help me. What shall we do with these letters once Szidonia and Gabor have spent a year or so deciphering them? Put them in a vault for safekeeping? Donate them to a museum? Let the ink slowly fade and the paper disintegrate until there’s nothing left? Or shall I use them as wallpaper?

I await your response, by mail, of course.

Juliet